Saturday, November 20, 2010

Because I Can

Come one and show me put me in shock...

Waiting for that crowd to flock,

Pounding on the floor as they knock.

They like to front "Like What You Want?"

Acting like mac's as they flaunt

So those are the Haters I like to taunt

If they fuck with me, for ever I will Haunt

This Pussy may be just a Skirt

But knows how to identify any Shirt

Got legs and an ass, know just how to Flirt

To get you laid down under in the Dirt!

So I have told you my anthem that's How We Do!

I'm one of those Bitches who'll always be true.

Hanging out with the most solid boys in the Crew.

The one to raise Hell all the way through!

Friday, November 19, 2010

therez sister

The Trickster, the game of Bingo, and the comic elements in "The Rez Sisters"

">

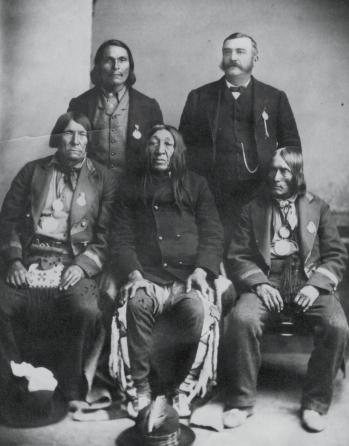

Chief Ahtahkakoop (Starblanket) led his people through the difficult transition from hunter and warrior to farmer, and from traditional Indian spiritualism to Christianity during the last third of the 19th century. A Plains Cree, Ahtahkakoop was born in the Saskatchewan River country in 1816. He was raised during the era when millions of buffalo roamed the northern plains and parklands, and developed into a noted leader, warrior, and buffalo hunter. By the 1860s, the buffalo were rapidly disappearing and newcomers arrived in greater numbers each year. Ahtahkakoop realized that the Children and grandchildren in his band would have to adopt a new way of living if they were to survive. Accordingly, in 1874 the chief invited Anglican missionary John Hines to settle with his people at Sandy Lake (Hines Lake), situated northwest of present-day Prince Albert. Two years later, Ahtahkakoop officially chose this land for his reserve. Ahtahkakoop was the second chief to sign Treaty 6 at Fort Carlton in 1876. Supported by the chief and his headmen, Hines established a school for the children and taught their parents how to farm. The children did well in school. Two of Hines’ first students, Ahtahkakoop’s nephews, became qualified teachers, and two great-nephews were ordained as Anglican priests. Hines prepared the adults for baptism; gradually most families converted to Christianity. Meanwhile, the families were increasing the number of acres cultivated and sown, raising herds of cattle, and building substantial homes. Unfortunately, the crops were often destroyed by frost, Hail, and Drought. Hunting was poor, and the people sometimes starved despite their hard work; additionally, restrictive government policies made life difficult. Ahtahkakoop and his people remained neutral during the uprising of 1885, determined to honour the treaty signed nine years earlier. Ahtahkakoop died on December 4, 1896, and was buried on the reserve that was named after him.

Starblanket

News Release - May 15, 2008

STARBLANKET INQUEST

An inquest into the death of Tyrone Starblanket will be held June 9 and 10, 2008, at 10 a.m. at the Prince Albert Queen's Bench Courthouse, 1800 Central Avenue.

Mr. Starblanket, aged 20 years, died March 12, 2007, at Victoria Hospital, Prince Albert.

Section 19 of The Coroners Act, 1999, states that the Chief Coroner may direct that an inquest be held into the death of any person.

CULTURAL COLLISION AND MAGICAL

TRANSFORMATION:

THE PLAYS OF TOMSON HIGHWAY

Anne Nothof

In The Rez Sisters and Dry Lips Oughta Move to Kapuskasing, Tomson Highway places in violent juxtaposition the cultural and spiritual values of Native and non-Native Canadians. Although there is in some respects a cultural accommodation and a positive integration of some of the materialistic products of a White capitalistic society, the negative consequences of cultural collision are played out in the lives of the women and men who constitute the Native community of Wasaychigan Hill Indian Reserve, Manitoulin Island, Ontario. As Highway indicates in his notes to The Rez Sisters, "Wasaychigan" means "window" in Ojibway: the reserve functions in both plays as a metonym for Native communities across the country--looking out on the conspicuous indicators of an economically powerful White society, and looking in at its own signs of self-destruction and of self-preservation. From her vantage point "away up here" on the roof of her house, as she hammers on new shingles with her silver hammer, Pelajia Patchnose, the Rez Sister with the clearest vision and the widest perspective, can see "half of Manitoulin Island on a clear day." She can see signs of fecund family life behind Marie-Adele's white picket fence, and signs of negligence and irresponsibility in the garbage heap behind Big Joey's "dumpy little house"(2). Beyond the reservation, she can just barely make out the pulp mill at Espanola where her husband works, and if she had binoculars she could see the superstack in Sudbury; if she were Superwoman, she could see the CN Tower in Toronto, where two of her sons work. The life of her family, then, extends beyond that of the reservation and finds a degree of accommodation beyond its parameters. Pelajia is also well aware of the spiritual and social problems on the Rez, and considers the possibility of a revolution in which the white male authority of church and state is overthrown:

Everyone here's crazy. No jobs. Nothing to do but drink and screw each other's wives and husbands and forget about our Nanabush (6).

Moreover, "the old stories, the old language" are "almost all gone" (5). Paradoxically, however, Pelajia also recalls with nostalgia a great bingo-player of the past who functions for her as social icon. She focuses on any positive indicator of survival and empowerment, regardless of its origins, and she both bullies and inspires the other six Rez sisters, all of whom struggle with ways to survive in a fragmented society.

In Dry Lips Oughta Move to Kapuskasing, Tomson Highway focuses on the lives of seven Native men in the Wasaychigan Reserve. The consequences of cultural collision are more radical and destructive in his second play of a projected seven play cycle, as the men of the Rez act out their anger and frustration, the consequences of their disempowerment, in violent, self-negating acts, or through denial and escape into alcoholism. In both plays, however, Highway shows the potential for healing in terms of a transformation which comes as a consequence of living through the cultural nightmare, and waking to discover the possibility of a new beginning. In the process of exploring the problems which are destroying Native society, self-destruction is obviated, and a transformation envisioned:

I think that every society is constantly in a state of change, of transformation, of metamorphoses. I think it is very important that it continue to be so to prevent the stagnation of our imaginations, our spirits, our soul.... What I really find fascinating about the future of my life, the life of my people, the life of my fellow Canadians is the searching for this new voice, this new identity, this new tradition, this magical transformation that potentially is quite magnificent. It is the combination of the best of both worlds ... combining them and coming up with something new. (Highway "Interview" 354)

Highway rejects nothing in his experience of both Native and non-Native society--the negative as well as the positive consequences of cultural collision and cultural bridging fuel the transformation.

In both The Rez Sisters and Dry Lips Oughta Move to Kapuskasing there are graphic and brutal realizations of the collision of cultures, when they assume oppositional values. The conflict is the result of a refusal to accommodate differences, and a desire to assert power and control through an annihilation of these differences. But the recognition of differences is not necessarily a conception of cultures in essentializing terms, as Sheila Rabillard argues in her post-colonial analysis of the two plays as "hybridizations."1 In Highway's plays there is no concept of "pure" cultures. The Rez comprises both Native and non-Native worlds, a variety of cultural patterns and experiences; these worlds collide when differences are not accommodated.

Even in a simplified account of the plot of The Rez Sisters, a cultural mélange is evident. The seven women--sisters, half-sisters, step-sisters--all hope to realize their particular dreams by winning the jackpot at "Biggest Bingo in the World" in Toronto. The means, then, is heavily compromised by non-White popular culture, and even the ends--the women's goals--are pervasively in terms of materialistic White society: Pelajia wants paved roads for the Rez, her sister Philomena wants an indoor bathroom with a large white toilet on which she can enthrone herself; Annie, who is infatuated with a Jewish country singer, wants the biggest record-player in the world on which to play country music; Veronique, who is infatuated with doctrinal Christianity, wants the biggest stove on the Rez. These short-term goals are primarily unconscious tactics for psychological survival, providing a way of addressing physical needs and of ameliorating current living conditions. They represent an accommodation with White society, but cannot address the consequences of cultural collision. The negative consequences of the opposition of cultural codes are manifested in the "so many things" that each woman has to forget: Emily Dictionary was beaten daily by her husband of ten years before she left him--the implication being that violent male behaviour is the result of alcohol abuse, which itself is a consequence of cultural collision. Philomena was abandoned by a White lover, and had to give up her baby; as a result she does not know who her child is--a clear indicator of loss of cultural identity Zhaboonigan, Veronique's mentally disabled adopted daughter, has been raped by a gang of White boys. She relives this rape in the play at a point when the other women are in a state of anarchic conflict before they finally resolve to work together to raise the necessary money for the trip to Toronto. Highway cuts through the comic mayhem with a graphic account of rape which is an undeniable indicator of the violence inflicted on one Native woman. Rape may function as a metaphor for the intrusive, destructive impact of one society on another in this play, as it does in Dry Lips, but it is also a cruel fact: Zhaboonigan (whose name means "needle" or "going-through-things") was assaulted by two White boys with a screwdriver, and left bleeding by the side of the road. Highway has explained in a talk at the University of Victoria in 1992 that this rape is based on an event which took place in a small town in Manitoba: Helen Betty Osborne, a young Native girl, was gang-raped and murdered by young White men--and penetrated fifty-six times with a screwdriver. (24; Note #13) Although many people in the town knew about the incident, only one youth of the four was brought to trial, and received a very light sentence.

Cultural collision is also strongly indicated in another recollection of violence suffered by a Native woman in The Rez Sisters. After leaving her abusive husband, Emily Dictionary joins a gang of Native lesbian "biker chicks" in San Francisco, one of whom, Rose, has been driven to self-destruction by her experience of "how fuckin hard it is to be an Indian in this country" (97). Refusing to give way, to give in, she drives her bike down the middle of the highway, and goes head-on into a big 18-wheeler--a graphic symbol for the destructive force of a dominant culture. Emily, however, with the spray of her lover's blood on her neck, drives on "straight into daylight," back to her home on the Wasaychigan Reserve. She has no urge to self-destruct through direct confrontation. And it is Emily Dictionary who conceives a baby in a one-night stand with the Rez stud, Big Joey. A form of transformation is effected through this promise of a new life, in which Zhabooningan in particular takes great pleasure. Highway is uncompromisingly idealistic in his hope for an improved life in the next generation of children, whom he sees as "magical" in their possibilities. Similarly, in Dry Lips Oughta Move to Kapuskasing, hope for the future is embodied in a baby girl. The last sound heard in the theatre, in the darkness, "is the baby's laughing voice, magnified on tape to fill the entire theatre" (130).2

In The Rez Sisters, the many children of Marie-Adele--fourteen in total (the number seven and its multiples recur in Highway's plays, having mystical significance in Native mythology)--also suggest the possibility of a flourishing Native culture. And the tragic, ironic death of Marie-Adele of ovarian cancer is also constructed as a magical transformation. Through the agency of the shape-shifter, Nanabush, she is brought to an acceptance of her death, and its horror and cruelty metamorphose into a welcoming of the "ever soft wings" which provide a final relief from her pain. Nanabush, the trickster figure in both The Rez Sisters and Dry Lips Oughta Move to Ktqmskasing, teaches the meaning of existence on earth by embodying its many contradictions. Death is cruel and final, but it is also a transformation--part of the continuing cycle of life, as Raven, another trickster figure, suggests in Lee Maracle's novel, Ravensong:

"Death is transformative," Raven said to earth from the depths of the ocean. The sound rolled out, amplifying slowly. Earth heard Raven speak. She paid no attention to the words; she let the compelling power of them play with her sensual self. Her insides turned, a hot burning sensation flitted about the stone of her. Earth turned, folded in on herself, a shock of heat shot through her. It changed her surface, the very atmosphere surrounding her changed. (85)

The shape-shifting, transformative powers of Nanabush are evident in his or her many manifestations (Grant 110). In The Rez Sisters, Nanabush, played by a male dancer, manifests himself as a seagull, a nighthawk, and the Bingo Master, moving between the extremes of white and black, hope and despair~ comedy and tragedy, order and chaos, as well as between Native and White cultures. Because Nanabush participates in both cultures, elements of each may be accommodated, without a necessary mutual destruction. The Rez Sisters concludes with Philomena sitting like a queen on her "spirit white" toilet throne, celebrating the black and white "large, shining porcelain tiles" (117) of her bathroom, and Pelajia back on her roof, still looking for the seagulls over Marie-Adele's house, unaware that Nanabush is right behind her, dancing "to the beat of her hammer, merrily and triumphantly" (118) in celebration of the strange inconsistencies and contradictions in individual lives.

In Dry Lips Oughta Move to Kapuskasing, it is Simon Starblanket, Marie-Adele's son, who dies, apparently needlessly and tragically. In Dry Lips, which Highway has described as the "flip side" to The Rez Sisters, the lives of seven men on the reserve are shown in terms of their response to the lives of the women, who have decided to form a hockey team--the Waspy Wailerettes--as a form of assertion of solidarity and empowerment. Most of the men are casualties of the collision with White society--disempowered, irresponsible, self-destructive. Big Joey, who is regarded by the women, and who regards himself as the Rez stud, is the least responsible, denying his paternity, and blaming the women for his powerlessness. His participation at Wounded Knee in South Dakota, which has become a metonym for the collision of White and Native cultures, has left him spiritually castrated:

"This is the end of the suffering of a great nation!" That was me. Wounded Knee, South Dakota, Spring of '73. The FBI. They beat us to the ground. Again and again and again. Ever since that spring, I've had these dreams where blood is spillin' out from my groin, nothin' there but blood and emptiness. It's like ... I lost myself. (119-20)

His unacknowledged son, Dickie Bird Halked, was born in a bar, and suffers the mentally debilitating effects of fetal alcohol syndrome, the most telling one being that he cannot speak: he has no language with which to articulate his pain and frustration, or to communicate with others. Moreover, he is unsure of his paternity--his origins. Pierre St. Pierre, the clown of the Rez, especially as interpreted by Graham Greene in productions at Theatre Passe Muraille and the Royal Alexandra Theatre in Toronto, is an ineffectual alcoholic, whose good intentions become confused and misdirected. Spooky Lacroix has substituted an addiction to Christianity for an addiction to alcohol, and uses his religion to intimidate the more emotionally and psychologically vulnerable. His distorted views of White inculcated values are radically juxtaposed with the Native spirituality of Simon Starblanket, whose last name reifies the positive nature of his quest for the spiritual beliefs of his ancestors. With his pregnant girlfriend, the granddaughter of a medicine woman, he intends to visit South Dakota, the site of Native suppression, to celebrate the renaissance of Native culture by dancing with the Sioux. Although he lacks mentors, Simon tries to learn to dance and chant, and "the magical flickering of [his] luminescent powwow dancing bustle," which is doubled and amplified by a dancing bustle worn by Nanabush (38), provides an oppositional symbol to the death-dealing cross held like a weapon by Spooky Lacroix, also aptly named. In fact, as the play shows, Christian priests have tried to eradicate Native spirituality and have demonized Native spiritual leaders. Spooky's cross becomes a literal weapon in the hands of Dickie Bird. Caught between the conflicting claims of Christianity and Native spirituality, obsessed by the potency of the cross, he rapes Simon's pregnant girlfriend with it. As in The Rez Sisters, rape has metaphorical implications--the rape of Native culture by White culture--but because in Dry Lips it is enacted, rather than described, it takes on a physical reality which is profoundly disturbing. Highway confounds the pervasive comedic direction of the play to expose the poison. The tragedy is compounded when Simon Starblanket, in a drunken rage, attempts to avenge the rape of Patsy by shooting Dickie Bird, and accidentally shoots himself, distracted by a vision of Nanabush. As in The Rez Sisters, Nanabush is associated with the death of a positive life force in the play. Zachary, in a moment of anguish and despair, cries out against any presiding deity--Christian or Native--who would allow such suffering and loss:

Aieeeeeee Lord! God! God of the Indian! God of the Whiteman! God-Al-fucking-mighty! Whatever the fuck your name is. Why are you doing this to us? Why are you doing this to us? Are you up there at all? Or are you some stupid, drunken shit, out-of-your-mind-passed out under some great beer table up there in your stupid fucking clouds! Come down! Astum oota! ("Come down here!") Why don't you come down? I dare you to come down from your high-falutin' fuckin' shit-throne up there, come down and show us you got the guts to stop this stupid, stupid, stupid way of living. It's got to stop. It's got to stop. (116)

Nanabush's response is a mockery of any attempt to blame any "higher" deity, presumably because men and women are responsible for their own shit. Nanabush is a manifestation of the contradictions and complexities of life--a way of visualizing them in order to understand them, not a first cause:

Towards the end of this speech, a light comes up on Nanabush. Her perch (i.e., the jukebox) has swivelled around and she is sitting on a toilet having a good shit. He/she is dressed in an old man's white beard and wig, but also wearing sexy, elegant women's high-heeled pumps. Surrounded by white, puffy clouds, she/he sits with her legs crossed, nonchalantly filing hislher fingernails. (117)

The figure of Nanabush embodies the extremities of the cultural conflict--and the paradoxes inherent in life and death. In Dry Lips, Nanabush is played by a woman, and acts out the roles of all the women in the play--the casualties of cultural collision, and the transformative possibilities. As Patsy, Simon's girlfriend, Nanabush is brutally raped; as Lady Black Halked, she gives birth to Dickie Bird astride a jukebox; as Hera Keechigeesik, whose names allude to the Greek goddess of heaven, she is the wife of Zachary Jeremiah, the Rez brother who is working towards an improved quality of life by opening a bakery, in which he will bake cookies called Nanabush. More significantly, as the mother of his child, she embodies hope for the future.

The magical transformative properties of Nanabush are suggested in production through lighting and music, and by her presiding location on the stage. She is perched on top of "a magical mystical jukebox" which is revealed at moments of transformation in the play--the birth of Dickie Bird, and the apotheosis of Simon Starblanket,3 whose vision of the moon is realized through a transformation of the jukebox--the popular culture of one society eliding with the mystical beliefs of another. In the Production Note included with the published play, Highway underscores the magical properties of the jukebox:

The effect sought after here is of this magical, mystical jukebox hanging in the night air, like a haunting and persistent memory, high up over the village of Wasaychigan Hill. (9-10)

Finally, as in The Rez Sisters, this magical transformation is celebrated by a dance in dream-life:

Out of this darkness emerges the sound of Simon Starblanket's chanting voice. Away up over Nanabush's perch, the moon begins to glow, fully and magnificently. Against it, in silhouette, we see Simon, wearing his powwow bustle. Simon Starblanket is dancing in the moon. (120)

As Highway has indicated, Nanabush is fundamental to the dream-life of Native culture, which in effect constitutes the play: Zachary awakens at the end to discover its truth. He has dreamed the whole sequence of comic and tragic events while lying on the couch in his own home. The transformation is effected through a framing of the play as dream, and a waking into the possibility for a brighter future, which as "the magical, silvery Nanabush laugh" (130) of Hera suggests, holds out more promise. The frame, however, does not mitigate the horrific and brutal events of the "dream." Their dramatization is more powerful than the comforting conclusion, and the transformation as a result remains hypothe tical.4 Highway's plays have been performed before diverse audiences of Natives and non-Natives, been produced in mainstream theatres and on the main stage at an international festival in Edinburgh. Ironically, they have succeeded in bridging the gap between the cultures by dramatizing their collision, and effecting a "transformation" of response to Native culture.5

NOTES

1 Drawing on the definitions of Homi K. Bhabha, Sheila Rabillard, in an insightful and comprehensive analysis, sees Tomson Highway's plays in terms of the "hybrid": "a space of colonial discourse in which the insignia of authority becomes a mask, a mockery, a space which has been systematically denied by both colonialists and nationalists who have sought authority in the authenticity of 'origins'. It is precisely as a separation from 'origins' and 'essences' that this colonial space is constructed." ("Absorption, Elimination, and the Hybrid. Some Impure Questions of Gender and Culture in the Trickster Drama of Tomson Highway," Essays in Theatre 12.1 [Nov 1993]: 4.)

2 According to Highway, "Legend has it that the shamans, who predicted the arrival of the white man and the near-destruction of the Indian people, also foretold the resurgence of the native people seven lifetimes after Columbus. We are that seventh generation." (quoted in Nancy Wigston, "Nanabush in the City," Books in Canada 18.2: 9)

3 This apotheosis bears some resemblance to the final vision of the murdered young protagonist in Judith Thompson's Lion in the Streets (1992). Perhaps "magical transformations" are now seen as the only way in which substantive change can be effected in increasingly complex societies.

4 Sheila Rabillard reaches a similar conclusion in her essay:

The play's dream world is coloured by the nightmare of alcoholism and despair, and Zachary's awakening at the close to a placid domestic realm of wife and child contrasts so strongly with the tone of the play's dreamscape as to seem itself a merely visionary hope (19).

5 Tomson Highway was astonished at the success of his Rez plays, but believed that the greatest accomplishment of The Rez Sisters was that "it raised public consciousness of a specific segment of the women's community--Indian women and older women at that." (quoted from Jennifer Preston, "Weesagediak Begins to Dance: Native Earth Performing Arts Inc.", The Drama Review 9:1/2 (1987): 143-44.

Robert Nunn speculates on the position of Highway's place in respect to mainstream Canadian theatre in "Marginality and English-Canadian Theatre." Theatre Research International 17 (1992): 217-25.

WORKS CITED

Grant, Agnes. "Native Drama: A Celebration of Native Culture," Contemporary Issues in Canadian Drama. Winnipeg: Blizzard, 1995.

Highway, Tompson. The Rez Sisters. Saskatoon: Fifty House, 1988.

---. Dry Lips Oughta Move to Kapuskasing. Saskatoon: Fifty House, 1989.

---. "Tomson Highway Interview." Other Solitudes: Canadian Multicultural Fictions. By Ann Wilson. Ed. Linda Hutcheon and Marion Richmond. Toronto: Oxford UP, 1990.

Maracle, Lee. Ravensong. Vancouver: Press Gang, 1993.

Rabillard, Sheila. "Absorption, Elimination, and the Hybrid: Some Impure Questions of Gender and Culture in the Trickster Drama of Tornson Highway." Essays in Theatre 12.1 (Nov. 1993).

Wigston, Nancy. "Nanabush in the City." Books in Canada. 18.2: 7-9

I had more or less given up, accepting that facile, spellbinding storytelling wasn't among my gifts, until I saw the new StoryWorld, by John and Caitlin Matthews. It's an originally British package of beautifully illustrated cards, very much in the style of tarot cards, each featuring a character ("The Mother", "The Youngest Daughter," "The Cat"), a location ("The Castle"), or a magical/potentially magical thing or place ("The Magic Mirror," "The Door to Faeryland," "The Star Blanket"). Each contains a few leading questions on the back ("Where is the cat going on this starry night?"), as well as a number of suitably ambiguous happenings in the background of the illustration on the front.

Intelligent Design (ID)

Adherents of ID claim it stands on equal footing with the current scientific theories regarding the origin of life and the origin of the universe. This claim has not been accepted by the scientific community and intelligent design does not constitute a research program within the science of biology. Despite ID sometimes being refered to popularly and in the media as "Intelligent Design Theory", it is not recognized as a scientific theory and has been categorized by the mainstream scientific community as creationist pseudoscience.

The National Academy of Sciences has said that Intelligent Design "and other claims of supernatural intervention in the origin of life" are not science because their claims cannot be tested by experiment and propose no new hypotheses of their own.

Critics argue that ID proponents find gaps within current evolutionary theory and fill them in with speculative beliefs, and that ID in this context may ultimately amount to the "God of the gaps".

Both the Intelligent Design concept and the associated movement have come under considerable criticism.

This criticism is regarded by advocates of ID as a natural consequence of philosophical naturalism which precludes by definition the possibility of supernatural causes as rational scientific explanations. As has been argued before in the context of the creation-evolution controversy, proponents of ID make the claim that there is a systemic bias within the scientific community against proponents' ideas and research based on the naturalistic assumption that science can only make reference to natural causes.Media organizations often focus on other qualities that the designer(s) in Intelligent Design theory might have in addition to intelligence, e.g., "higher power", "unseen force", etc.

Intelligent Design is presented as an alternative to purely naturalistic forms of the theory of evolution. Its putative main purpose is to investigate whether or not the empirical evidence necessarily implies that life on Earth must have been designed by an intelligent agent or agents.

For example, William Dembski, one of ID's leading proponents, has stated that the fundamental claim of ID is that "there are natural systems that cannot be adequately explained in terms of undirected natural forces and that exhibit features which in any other circumstance we would attribute to intelligence."

Proponents of ID look for evidence of what they call signs of intelligence - physical properties of an object that imply "design". The most common cited signs being considered include irreducible complexity, information mechanisms, and specified complexity.

Many design theorists believe that living systems show one or more of these, from which they infer that life is designed. This stands in opposition to mainstream explanations of systems, which explain the natural world exclusively through impersonal physical processes such as random mutations and natural selection.

ID proponents claim that while evidence pointing to the nature of an "Intelligent Designer" may not be observable, its effects on nature can be detected. Dembski, in Signs of Intelligence claims "Proponents of intelligent design regard it as a scientific research program that investigates the effects of intelligent causes. Note that intelligent design studies the effects of intelligent causes and not intelligent causes per se."

In his view questions concerning the identity of a designer fall outside the realm of the idea.Critics call ID religious dogma repackaged in an effort to return creationism into public school science classrooms and note that ID features notably as part of the campaign known as Teach the Controversy.

The National Academy of Sciences and the National Center for Science Education assert that ID is not science, but creationism.

While the scientific theory of evolution by natural selection has observable and repeatable facts to support it such as the process of mutations, gene flow, genetic drift, adaptation and speciation through natural selection, the "Intelligent Designer" in ID is neither observable nor repeatable.

Critics argue this violates the scientific requirement of falsifiability. Indeed, ID proponent Behe concedes "You can't prove intelligent design by experiment". [8]Critics say ID is attempting to redefine natural science.

They cite books and statements of principal ID proponents calling for the elimination of "methodological naturalism" from science and its replacement with what critics call "methodological supernaturalism", which means belief in a transcendent, non-natural dimension of reality inhabited by a transcendent, non-natural deity.

Natural science uses the scientific method to create a posteriori knowledge based on observation alone (sometimes called empirical science). Critics of ID consider the idea that some outside intelligence created life on Earth to be a priori (without observation) knowledge.

ID proponents cite some complexity in nature that cannot yet be fully explained by the scientific method. (For instance, abiogenesis, the generation of life from non-living matter, is not yet understood scientifically, although the first stages have been reproduced in the Miller-Urey experiment.) ID proponents infer that an intelligent designer is behind the part of the process that is not understood scientifically. Since the designer cannot be observed, critics continue, it is a priori knowledge.

This allegedly a priori inference that an intelligent designer (a god or an alien life force[12]) created life on Earth has been compared to the a priori claim that aliens helped the ancient Egyptians build the pyramids.

In both cases, the effect of this outside intelligence is not repeatable, observable, or falsifiable, and it violates Occam's Razor as well. From a strictly empirical standpoint, one may list what is known about Egyptian construction techniques, but must admit ignorance about exactly how the Egyptians built the pyramids.

The phrase intelligent design, used in this sense, first appeared in Christian creationist literature, including the textbook Of Pandas and People (Haughton Publishing Company, Dallas, 1989). The term was promoted more broadly by the retired legal scholar Phillip E. Johnson following his 1991 book Darwin on Trial. Johnson is the program advisor of the Center for Science and Culture and is considered the father of the intelligent design movement.However, for millenia, philosophers have argued that the complexity of nature indicates supernatural design; this has come to be known as the teleological argument.

The most notable forms of this argument were expressed by Thomas Aquinas in his Summa Theologica (thirteenth century), design being the fifth of Aquinas' five proofs for God's existence, and William Paley in his book Natural Theology (nineteenth century) where he makes his watchmaker analogy. The modern concept of intelligent design is distinguished from the teleological argument in that ID does not identify the agent of creation.

Intelligent design arguments are carefully formulated in secular terms and intentionally avoid positing the identity of the designer.

Phillip E. Johnson has stated that cultivating ambiguity by employing secular language in arguments which are carefully crafted to avoid overtones of theistic creationism is a necessary first step for ultimately reintroducing the Christian concept of God as the designer. Johnson emphasizes "the first thing that has to be done is to get the Bible out of the discussion" and that "after we have separated materialist prejudice from scientific fact... only then can "biblical issues" be discussed."

Johnson explicitly calls for ID proponents to obfuscate their religious motivations so as to avoid having ID identified "as just another way of packaging the Christian evangelical message."

Though not all ID proponents are motivated by religious fervor, the majority of the principal ID advocates (including Michael Behe, William Dembski, Jonathan Wells, and Stephen C. Meyer) are Christians and have stated that in their view the designer of life is clearly God. The preponderance of leading ID proponents are evangelical Protestants.

The conflicting claims made by leading ID advocates as to whether or not ID is rooted in religious conviction are the result of their strategy. For example, William Dembski in his book The Design Inference lists a god or an "alien life force" as two possible options for the identity of the designer. However, in his book Intelligent Design; the Bridge Between Science and Theology Dembski states that "Christ is indispensable to any scientific theory, even if its practitioners don't have a clue about him.

The pragmatics of a scientific theory can, to be sure, be pursued without recourse to Christ. But the conceptual soundness of the theory can in the end only be located in Christ."

Dembski also stated "ID is part of God's general revelation..." "Not only does intelligent design rid us of this ideology (materialism), which suffocates the human spirit, but, in my personal experience, I've found that it opens the path for people to come to Christ."

The Intelligent design movement is an organized campaign to promote ID arguments in the public sphere, primarily in the United States. The movement claims ID exposes the limitations of scientific orthodoxy, and of the secular philosophy of Naturalism. ID movement proponents allege that science, by relying upon naturalism, demands an adoption of a naturalistic philosophy that dismisses out of hand any explanation that contains a supernatural cause. Phillip E. Johnson, considered the father of the intelligent design movement and its unofficial spokesman stated that the goal of intelligent design is to cast creationism as a scientific concept.

The intelligent design movement is largely the result of efforts by the conservative Christian think tank the Discovery Institute, and its Center for Science and Culture. The Discovery Institute's wedge strategy and its adjunct, the Teach the Controversy campaign, are campaigns intended to sway the opinion of the public and policymakers. They target public school administrators and state and federal elected representatives to introduce intelligent design into the public school science curricula and marginalize mainstream science. The Discovery Institute acknowledges that private parties have donated millions for a research and publicity program to "unseat not just Darwinism, but also Darwinism's cultural legacy."

Critics note that instead of producing original scientific data to support ID¹s claims, the Discovery Institute has promoted ID politically to the public, education officials and public policymakers. Also oft mentioned is that there is a conflict between what leading ID proponents tell the public through the media and what they say before their conservative Christian audiences, and that the Discovery Institute as a matter of policy obfuscates its agenda. This they claim is proof that the movement's "activities betray an aggressive, systematic agenda for promoting not only intelligent design creationism, but the religious worldview that undergirds it."

Richard Dawkins, biologist and professor at Oxford University, compares "Teach the controversy" with teaching flat earthism, perfectly fine in a history class but not in science. "If you give the idea that there are two schools of thought within science, one that says the Earth is round and one that says the Earth is flat, you are misleading children."

Underscoring claims that the ID movement is more social and political enterprise than a scientific one, intelligent design has been in the center of a number of controversial political campaigns and legal challenges. These have largely been attempts to introduce intelligent design into public school science classrooms while concurrently portraying evolutionary theory as a theory largely scientifically disputed; a "theory in crisis." This has been despite a consensus in the scientific community that ID lacks merit and ID proponents have yet to propose an actual scientific hypothesis. These campaigns and cases are discussed in depth in the Intelligent design movement article.

Capital

Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts of 1844

Profit of Capital

1. Capital

What is the basis of capital, that is, of private property in the products of other men's labour?

“Even if capital itself does not merely amount to theft or fraud, it still requires the cooperation of legislation to sanctify inheritance.” (Say, Traité d'economie politique.)[9]

How does one become a proprietor of productive stock? How does one become owner of the products created by means of this stock?

By virtue of positive law. (Say.)

What does one acquire with capital, with the inheritance of a large fortune, for instance?

“The person who [either acquires, or] succeeds to a great fortune, does not necessarily [acquire or] succeed to any political power [.... ] The power which that possession immediately and directly conveys to him, is the power of purchasing; a certain command over all the labour, or over all the produce of labour, which is then in the market.” (Wealth of Nations, by Adam Smith, Vol. I, pp. 26-27.)[10]

Capital is thus the governing power over labour and its products. The capitalist possesses this power, not on account of his personal or human qualities, but inasmuch as he is an owner of capital. His power is the purchasing power of his capital, which nothing can withstand.

Later we shall see first how the capitalist, by means of capital, exercises his governing power over labour, then, however, we shall see the governing power of capital over the capitalist himself.

What is capital?

“A certain quantity of labour. stocked and stored up to be employed.” (Adam Smith, op. cit., Vol. I, p. 295.)

Capital is stored-up labour.

(2) Fonds, or stock, is any accumulation of products of the soil or of manufacture. Stock is called capital only when it yields to its owner a revenue or profit. (Adam Smith, op. cit., p. 243)

2. The Profit of Capital

The profit or gain of capital is altogether different from the wages of labour. This difference is manifested in two ways: in the first place, the profits of capital are regulated altogether by the value of the capital employed, although the labour of inspection and direction associated with different capitals may be the same. Moreover in large works the whole of this labour is committed to some principal clerk, whose salary bears no regular proportion to the capital of which he oversees the management. And although the labour of the proprietor is here reduced almost to nothing, he still demands profits in proportion to his capital. (Adam Smith, op. cit., Vol. I, p. 43)[11]

Why does the capitalist demand this proportion between profit and capital?

He would have no interest in employing the workers, unless he expected from the sale of their work something more than is necessary to replace the stock advanced by him as wages and he would have no interest to employ a great stock rather than a small one, unless his profits were to bear some proportion to the extent of his stock. (Adam Smith, op. cit., Vol. I, p. 42)

The capitalist thus makes a profit, first, on the wages, and secondly on the raw materials advanced. by him.

What proportion, then, does profit bear to capital?

If it is already difficult to determine the usual average level of wages at a particular place and at a particular time, it is even more difficult to determine the profit on capitals. A change in the price of the commodities in which the capitalist deals, the good or bad fortune of his rivals and customers, a thousand other accidents to which commodities are exposed both in transit and in the warehouses — all produce a daily, almost hourly variation in profit. (Adam Smith, op. cit., Vol. I, pp. 78-79)

But though it is impossible to determine with precision what are the profits on capitals, some notion may be formed of them from the interest of money. Wherever a great deal can be made by the use of money, a great deal will be given for the use of it; wherever little can be made by it, little will be given. (Adam Smith, op. cit., Vol. I, p. 79)

The proportion which the usual market rate of interest ought to bear to the rate of clear profit, necessarily varies as profit rises or falls. Double interest is in Great Britain reckoned what the merchants call a good, moderate, reasonable profit, terms which mean no more than a common and usual profit. (Adam Smith, op. cit., Vol. I, p. 87)

What is the lowest rate of profit? And what the highest?

The lowest rate of ordinary profit on capital must always be something more than what is sufficient to compensate the occasional losses to which every employment of stock is exposed. It is this surplus only which is neat or clear profit. The same holds for the lowest rate of interest. (Adam Smith, op. cit., Vol. I, p. 86)

The highest rate to which ordinary profits can rise is that which in the price of the greater part of commodities eats up the whole of the rent of the land, and reduces the wages of labour contained in the commodity supplied to the lowest rate, the bare subsistence of the labourer during his work. The worker must always be fed in some way or other while he is required to work; rent can disappear entirely. For example: the servants of the East India Company in Bengal. (Adam Smith, op. cit., Vol. I, pp. 86-87)

Besides all the advantages of limited competition which the capitalist may exploit in this case, he can keep the market price above the natural price by quite decorous means.

For one thing, by keeping secrets in trade if the market is at a great distance from those who supply it, that is, by concealing a price change, its rise above the natural level. This concealment has the effect that other capitalists do not follow him in investing their capital in this branch of industry or trade.

Then again by keeping secrets in manufacture, which enable the capitalist to reduce the costs of production and supply his commodity at the same or even at lower prices than his competitors while obtaining a higher profit. (Deceiving by keeping secrets is not immoral? Dealings on the Stock Exchange.) Furthermore, where production is restricted to a particular locality (as in the case of a rare wine), and where the effective demand can never he satisfied. Finally, through monopolies exercised by individuals or companies. Monopoly price is the highest possible. (Adam Smith, op. cit., Vol. I, pp. 53-54)

Other fortuitous causes which can raise the profit on capital:

The acquisition of new territories, or of new branches of trade, often increases the profit on capital even in a wealthy country, because they withdraw some capital from the old branches of trade, reduce competition, and cause the market to be supplied with fewer commodities, the prices of which then rise: those who deal in these commodities can then afford to borrow at a higher rate of interest. (Adam Smith, op. cit., Vol. I, p. 83)

The more a commodity comes to be manufactured — the more it becomes an object of manufacture — the greater becomes that part of the price which resolves itself into wages and profit in proportion to that which resolves itself into rent. In the progress of the manufacture of a commodity, not only the number of profits increases, but every subsequent profit is greater than the foregoing; because the capital from which it is derived must always be greater. The capital which employs the weavers, for example, must always be greater than that which employs the spinners; because it not only replaces that capital with its profits, but pays, besides, the wages of weavers; and the profits must always bear some proportion to the capital. (op. cit., Vol. I, p. 45)

Thus the advance made by human labour in converting the product of nature into the manufactured product of nature increases, not the wages of labour, but in part the number of profitable capital investments, and in part the size of every subsequent capital in comparison with the foregoing.

More about the advantages which the capitalist derives from the division of labour, later.

He profits doubly — first, by the division of labour; and secondly, in general, by the advance which human labour makes on the natural product. The greater the human share in a commodity, the greater the profit of dead capital.

In one and the same society the average rates of profit on capital are much more nearly on the same level than the wages of the different sorts of labour. (op. cit., Vol. I, p. 100.) In the different employments of capital, the ordinary rate of profit varies with the certainty or uncertainty of the returns.

The ordinary profit of stock, though it rises with the risk, does not always seem to rise in proportion to it. (op. cit., Vol. I, pp. 99-100.)

It goes without saying that profits also rise if the means of circulation become less expensive or easier available (e.g., paper money).

3. The Rule of Capital over Labour and the Motives of the Capitalist

The consideration of his own private profit is the sole motive which determines the owner of any capital to employ it either in agriculture, in manufactures, or in some particular branch of the wholesale or retail trade. The different quantities of productive Labour which it may put into motion, and the different values which it may add to the annual produce of the land and labour of his country, according as it is employed in one or other of those different ways, never enter into his thoughts. (Adam Smith, (op. cit., Vol. I, p. 335)

The most useful employment of capital for the capitalist is that which, risks being equal, yields him the greatest profit. This employment is not always the most useful for society; the most useful employment is that which utilises the productive powers of nature. (Say, t. II, pp. 130-31.)

The plans and speculations of the employers of capitals regulate and direct all the most important operations of labour, and profit is the end proposed by all those plans and projects. But the rate of profit does not, like rent and wages, rise with the prosperity and fall with the decline of the society. On the contrary, it is naturally low in rich and high in poor countries, and it is always highest in the countries which are going fastest to ruin. The interest of this class, therefore, has not the same connection with the general interest of the society as that of the other two.... The particular interest of the dealers in any particular branch of trade or manufactures is always in some respects different from, and frequently even in sharp opposition to, that of the public. To widen the market and to narrow the sellers' competition is always the interest of the dealer.... This is a class of people whose interest is never exactly the same as that of society, a class of people who have generally an interest to deceive and to oppress the public. (Adam Smith, op. cit., Vol. I, pp. 231-32)

4. The Accumulation of Capitals and the Competition among the Capitalists

The increase of stock, which raises wages, tends to lower the capitalists' profit, because of the competition amongst the capitalists. (Adam Smith, op. cit., Vol. I, p. 78)

If, for example, the capital which is necessary for the grocery trade of a particular town “is divided between two different grocers, their competition win tend to make both of them sell cheaper than if it were in the hands of one only; and if it were divided among twenty, their competition would be just so much the greater, and the chance of their combining together, in order to raise the price, just so much the less”. (Adam Smith, op. cit., Vol. I, p. 322)

Since we already know that monopoly prices are as high as possible, since the interest of the capitalists, even from the point of view commonly held by political economists, stands in hostile opposition to society, and since a rise of profit operates like compound interest on the price of the commodity (Adam Smith, op. cit., Vol. I, pp. 87-88), it follows that the sole defence against the capitalists is competition, which according to the evidence of political economy acts beneficently by both raising wages and lowering the prices of commodities to the advantage of the consuming public.

But competition is only possible if capital multiplies, and is held in many hands. The formation of many capital investments is only possible as a result of multilateral accumulation, since capital comes into being only by accumulation; and multilateral accumulation necessarily turns into unilateral accumulation. Competition among capitalists increases the accumulation of capital. Accumulation, where private property prevails, is the concentration of capital in the hands of a few, it is in general an inevitable consequence if capital is left to follow its natural course, and it is precisely through competition that the way is cleared for this natural disposition of capital.

We have been told that the profit on capital is in proportion to the size of the capital. A large capital therefore accumulates more quickly than a small capital in proportion to its size, even if we disregard for the time being deliberate competition.

[12] Accordingly, the accumulation of large capital proceeds much more rapidly than that of smaller capital, quite irrespective of competition. But let us follow this process further.

With the increase of capital the profit on capital diminishes, because of competition. The first to suffer, therefore, is the small capitalist.

The increase of capitals and a large number of capital investments presuppose, further, a condition of advancing wealth in the country.

“In a country which had acquired its full complement of riches [ ... ]the ordinary rate of clear profit would he very small, so the usual [market] rate of interest which could be afforded out of it would be so low as to render it impossible for any but the very wealthiest people to live upon the interest of their money. All people of [...] middling fortunes would be obliged to superintend themselves the employment of their own stocks. It would be necessary that almost every man should be a man of business, or engage in some sort of trade.” (Adam Smith, op. cit., Vol. I, p. 86)

This is the situation most dear to the heart of political economy.

“The proportion between capital and revenue, therefore, seems everywhere to regulate the proportion between industry and idleness; wherever capital predominates, industry prevails; wherever revenue, idleness.” (Adam Smith, op. cit., Vol. I, p. 301.)

What about the employment of capital, then, in this condition of increased competition?

“As stock increases, the quantity of stock to he lent at interest grows gradually greater and greater. As the quantity of stock to he lent at interest increases, the interest ... diminishes (i) because the market price of things commonly diminishes as their quantity increases. ... and (ii) because with the increase of capitals in any country, “it becomes gradually more and more difficult to find within the country a profitable method of employing any new capital. There arises in consequence a competition between different capitals, the owner of one endeavouring to get possession of that employment which is occupied by another. But upon most occasions he can hope to jostle that other out of this employment by no other means but by dealing upon more reasonable terms. He must not only sell what he deals in somewhat cheaper, but in order to get it to sell, he must sometimes, too, buy it dearer. The demand for productive labour, by the increase of the funds which are destined for maintaining it, grows every day greater and greater. Labourers easily find employment, IIX, 2]but the owners of capitals find it difficult to get labourers to employ. Their competition raises the wages of labour and sinks the profits of stock.” (Adam Smith, op. cit., Vol. I, p. 316)

Thus the small capitalist has the choice: (1) either to consume his capital, since he can no longer live on the interest — and thus cease to be a capitalist; or (2) to set up a business himself, sell his commodity cheaper, buy dearer than the wealthier capitalist, and pay higher wages — thus ruining himself, the market price being already very low as a result of the intense competition presupposed. If, however, the big capitalist wants to squeeze out the smaller capitalist, he has all the advantages over him which the capitalist has as a capitalist over the worker. The larger size of his capital compensates him for the smaller profits, and he can even bear temporary losses until the smaller capitalist is ruined and he finds himself freed from this competition. In this way, he accumulates the small capitalist's profits.

Furthermore: the big capitalist always buys cheaper than the small one, because he buys bigger quantities. He can therefore well afford to sell cheaper.

But if a fall in the rate of interest turns the middle capitalists from rentiers into businessmen, the increase in business capital and the resulting smaller profit produce conversely a fall in the rate of interest.

“When the profits which can be made by the use of a capital are diminished the price which can be paid for the use of it [...] must necessarily be diminished with them.” (Adam Smith, loc. cit., Vol. I, p. 316)

“As riches, improvement, and population have increased, interest has declined”, and consequently the profits of capitalists, “after these [profits] are diminished, stock may not only continue to increase, but to increase much faster than before. [...] A great stock though with small profits, generally increases faster than a small stock with great profits. Money, says the proverb, makes money.” (op. cit., Vol. I, p. 83)

When, therefore, this large capital is opposed by small capitals with small profits, as it is under the presupposed condition of intense competition, it crushes them completely.

The necessary result of this competition is a general deterioration of commodities, adulteration, fake production and universal poisoning, evident in large towns.

An important circumstance in the competition of large and small capital is, furthermore, the relation between fixed capital and circulating capital.

Circulating capital is a capital which is “employed in raising” provisions, “manufacturing, or purchasing goods, and selling them again. [... ] The capital employed in this manner yields no revenue or profit to its employer, while it either remains in his possession, or continues in the same shape. [...] His capital is continually going from him in one shape, and returning to him in another, and it is only by means of such circulation, or successive exchanges” and transformations “that it can yield him any profit”. Fixed capital consists of capital invested “in the improvement of land, in the purchase of useful machines and instruments of trade, or in such-like things”. (Adam Smith, op. cit., Vol. I, pp. 243-44)

“Every saying in the expense of supporting the fixed capital is an improvement of the net revenue of the society. The whole capital of the undertaker of every work is necessarily divided between his fixed and7 his circulating capital. While his whole capital remains the same, the smaller the one part, the greater must necessarily be the other. It is the circulating capital which furnishes the materials and wages of labour, and puts industry into motion. Every saving, therefore, in the expense of maintaining the fixed capital, which does not diminish the productive powers of labour, must increase the fund which puts industry into motion.” (Adam Smith, op. cit., Vol. I, p. 257)

It is clear from the outset that the relation of fixed capital and circulating capital is much more favourable to the big capitalist than to the smaller capitalist. The extra fixed capital required by a very big banker as against a very small one is insignificant. Their fixed capital amounts to nothing more than the office. The equipment of the bigger landowner does not increase in proportion to the size of his estate. Similarly, the credit which a big capitalist enjoys compared with a smaller one means for him all the greater saving in fixed capital — that is, in the amount of ready money he must always have at hand. Finally, it is obvious that where industrial labour has reached a high level, and where therefore almost all manual labour has become factory labour, the entire capital of a small capitalist does not suffice to provide him even with the necessary fixed capital. As is well known, large-scale cultivation usually provides employment only for a small number of hands. [in French]

It is generally true that the accumulation of large capital is also accompanied by a proportional concentration and simplification of fixed capital, as compared to the smaller capitalists. The big capitalist introduces for himself some kind of organisation of the instruments of labour.

“Similarly, in the sphere of industry every manufactory and mill is already a comprehensive combination of a large material fortune with numerous and varied intellectual capacities and technical skills serving the common purpose of production.... Where legislation preserves landed property in large units, the surplus of a growing population flocks into trades, and it is therefore as in Great Britain in the field of industry, principally, that proletarians aggregate in great numbers. Where, however, the law permits the continuous division of the land, the number of small. debt-encumbered proprietors increases, as in France; and the continuing process of fragmentation throws them into the class of the needy and the discontented. When eventually this fragmentation and indebtedness reaches a higher degree still, big p small property, just as large-scale industry estates are formed again, large numbers of for the cultivation of the soil are again driven into industry”. (Schulz, Bewegung der Production, pp. 58, 59.)

“Commodities of the same kind change in character as a result of changes in the method of production, and especially as a result of the use of machinery. Only by the exclusion of human power has it become possible to spin from a pound of cotton worth 3 shillings and 8 pence 350 hanks of a total length of 167 English miles (i.e., 36 German miles), and of a commercial value of 25 guineas.” (op. cit., p. 62.)

“On the average the prices of cotton-goods have decreased in England during the past 45 years by eleven-twelfths, and according to Marshall's calculations the same amount of manufactured goods for which 16 shillings was still paid in 1814 is now supplied at 1 shilling and 10 pence. The greater cheapness of industrial products expands both consumption at home and the market abroad, and because of this the number of workers in cotton has not only not fallen in Great Britain after the introduction of machines but has risen from forty thousand to one and a half million. IIXII, 21 As to the earnings of industrial entrepreneurs and workers; the growing competition between the factory owners has resulted in their profess necessarily falling relative to the amount of products supplied by them. In the years 1820-33 the Manchester manufacturer's gross profit on a piece of calico fell from four shillings 1 1/3 pence to one shilling 9 pence. But to make up for this loss, the volume of manufacture has been correspondingly increased. The consequence of this is that separate branches of industry experience over-production to some extent, that frequent bankruptcies occur causing property to fluctuate and vacillate unstably within the class of capitalists and masters of labour, thus throwing into the proletariat some of those who have been ruined economically; and that, frequently and suddenly, close-downs or cuts in employment become necessary, the painful effects of which are always bitterly felt by the class of wage-labourers.” (op. cit., p. 63.)

“To hire out one's labour is to begin one's enslavement. To hire out the materials of labour is to establish one's freedom.... Labour is man; the materials, on the other hand, contain nothing human.” (Pecqueur, Théorie sociale, etc.)

“The material element, which is quite incapable of creating wealth without the other element. labour, acquires the magical virtue of being fertile for them [who own this material element] as if by their own action they had placed there this indispensable element.” (op. cit.)

“Supposing that the daily labour of a worker brings him on the average 400 francs a year and that this sum suffices for every adult to live some sort of crude life, then any proprietor receiving 2,000 francs in interest or rent, from a farm, a house, etc., compels indirectly five men to work for him; an income of 100,000 francs represents the labour of 250 men, and that of 1,000,000 francs the labour of 2,500 individuals (hence, 300 million [Louis Philippe] therefore the labour of 750,000 workers).” (op. cit., pp. 412-13.)

'The human law has given owners the right to use and to abuse — that is to say, the right to do what their will with the materials of labour.... They are in no way obliged law to provide work for the propertyless when required and at all times, by or to pay them always an adequate wage, etc. (loc. cit., p. 413.) “Complete freedom concerning the nature, the quantity, the quality and the expediency of production; concerning the use and the disposal of wealth; and full command over the materials of all labour. Everyone is free to exchange what belongs to him as he thinks fit, without considering anything other than his own interest as an individual” (op. cit. p. 413.)

“Competition is merely the expression of the freedom to exchange, which itself is the immediate and logical consequence of the individual's right to use and abuse all the instruments of production. The right to use and abuse, freedom of exchange, and arbitrary competition — these three economic moments, which form one unit, entail the following consequences; each produces what he wishes, as he wishes, when he wishes, where he wishes, produces well or produces badly, produces too much or not enough, too soon or too late, at too high a price or too low a price; none knows whether he will sell, to whom he will sell, how he will Sen. when he will sell, where he will sell. And it is the same with regard to purchases. The producer is ignorant of needs and resources, of demand and supply. He sells when he wishes, when he can, where he wishes, to whom he wishes, at the price he wishes. And he buys in the same way. In all this he is ever the plaything of chance, the slave of the law of the strongest, of the least harassed, of the richest.... Whilst at one place there is scarcity, at another there is glut and waste. Whilst one producer sells a lot or at a very high price, and at an enormous profit, the other sells nothing or sells at a loss.... The supply does not know the demand, and the demand does not know the supply. You produce. trusting to a taste, a fashion, which prevails amongst the consuming public. But by the time you are ready to deliver the commodity, the whim has already passed and has settled on some other kind of product.... The inevitable consequences: bankruptcies occurring constantly and universally; miscalculations, sudden ruin and unexpected fortunes, commercial crises, stoppages, periodic gluts or shortages; instability and depreciation of wages and profits, the loss or enormous waste of wealth, time and effort in the arena of fierce competition.” (op. cit., pp. 414-16.)

Ricardo in his book [On the Principles of Political Economy and Taxation] (rent of land): Nations are merely production-shops; man is a machine for consuming and producing; human life is a kind of capital; economic laws blindly rule the world. For Ricardo men are nothing, the product everything. In the 26th chapter of the French translation it says:

“To an individual with a capital of £20,000 whose profits were £2,000 per annum, it would he a matter quite indifferent whether his capital would employ a hundred or a thousand men.... Is not the real interest of the nation similar? provided its net real income, its rent and profits be the same, it is of no importance whether the nation consists of ten or twelve millions of inhabitants.” — [t. II, pp. 194, 195.] “In fact, says M. Sismondi ([Nouveaux principes diconomie politique,] t. II, p. 331), nothing remains to be desired but that the King, living quite alone on the island, should by continuously turning a crank cause automatons to do all the work of England.”[13]

“The master who buys the worker's labour at such a low price that it scarcely suffices for the worker's most pressing needs is responsible neither for the inadequacy of the wage nor for the excessive duration of the labour: he himself has to submit to the law which he imposes.... Poverty is not so much caused by men as by the power of things.” b (Buret, op. cit., p. 82.)

“The inhabitants of many different parts of Great Britain have not capital sufficient to improve and cultivate all their lands. The wool of the southern counties of Scotland is, a great part of it, after a long land carriage through very bad roads, manufactured in Yorkshire, for want of capital to manufacture it at home. There are many little manufacturing towns in Great Britain, of which the inhabitants have not capital sufficient to transport the produce of their own industry to those distant markets where there is demand and consumption for it. If there are any merchants among them, they are properly only the agents of wealthier merchants who reside in some of the greater commercial cities.” (Adam Smith, Wealth of Nations, Vol. I, pp. 326-27)

“The annual produce of the land and labour of any nation can be increased in its value by no other means but by increasing either the number of its productive labourers, or the productive power of those labourers who had before been employed.... In either case an additional capital is almost always required.” (Adam Smith, op. cit., Vol. I, pp. 306-07)

“As the accumulation of stock must, in the nature of things, be previous to the division of labour, so labour can be more and more subdivided in proportion only as stock is previously more and more accumulated. The quantity of materials which the same number of people can work up, increases in a great proportion as labour comes to he more and more subdivided; and as the operations of each workman are gradually reduced to a greater degree of simplicity, a variety of new machines come to be invented for facilitating and abridging those operations. As the division of labour advances, therefore, in order to give constant employment to an equal number of workmen, an equal stock of provisions, and a greater stock of materials and tools than what would have been necessary in a ruder state of things, must be accumulated beforehand. But the number of workmen in every branch of business generally increases with the division of labour in that branch, or rather it is the increase of their number which enables them to class and subdivide themselves in this manner.” (Adam Smith, op. cit., Vol. I, pp. 241-42)

“As the accumulation of stock is previously necessary for carrying on this great improvement in the productive powers of labour, so that accumulation naturally leads to this improvement. The person who employs his stock in maintaining labour, necessarily wishes to employ it in such a manner as to produce as great a quantity of work as possible. He endeavours, therefore, both to make among his workmen the most proper distribution of employment, and to furnish them with the best machines [... ]. His abilities in both these respects] at V, 21 are generally in proportion to the extent of his stock, or to the number of people whom it can employ. The quantity of industry, therefore, not only increases in every country with the increase of the stock which em ploys it, but, in consequence of that increase, the same quantity of industry produces a much greater quantity of work.” (Adam Smith, op. cit., Vol. I, p. 242)

Hence over-production.

“More comprehensive combinations of productive forces ... in industry and trade by uniting more numerous and more diverse human and natural powers in larger-scale enterprises. Already here and there, closer association of the chief branches of production. Thus, big manufacturers will try to acquire also large estates in order to become independent of others for at least a part of the raw materials required for their industry; or they will go into trade in conjunction with their industrial enterprises, not only to sell their own manufactures, but also to purchase other kinds of products and to sell these to their workers. In England, where a single factory owner sometimes employs ten to twelve thousand workers ... it is already not uncommon to find such combinations of various branches of production controlled by one brain, such smaller states or provinces within the state. Thus, the mine owners in the Birmingham area have recently taken over the whole process of iron production, which was previously distributed among various entrepreneurs and owners, (See “Der bergmännische Distrikt bei Birmingham”, Deutsche Vierteljahr-Schrift No. 3, 1838.) Finally in the large joint-stock enterprises which have become so numerous, we see far-reaching combinations of the financial resources of many participants with the scientific and technical knowledge and skills of others to whom the carrying-out of the work is handed over. The capitalists are thereby enabled to apply their savings in more diverse ways and perhaps even to employ them simultaneously in agriculture, industry and commerce. As a consequence their interest becomes more comprehensive, and the contradictions between agricultural, industrial, and commercial interests are reduced and disappear. But this increased possibility of applying capital profitably in the most diverse ways cannot but intensify the antagonism between the propertied and the non-propertied classes.” (Schulz, op. cit., pp. 40-4l.)

The enormous profit which the landlords of houses make out of poverty. House rent stands in inverse proportion to industrial poverty.

So does the interest obtained from the vices of the ruined proletarians. (Prostitution, drunkenness, pawnbroking.)

The accumulation of capital increases and the competition between capitalists decreases, when capital and landed property are united in the same hand, also when capital is enabled by its size to combine different branches of production.

Indifference towards men. Smith's twenty lottery-tickets.[14]

Say's net and gross revenue.

Random copy

Enoch was a prophet who allegedly lived from 3284-3017 B. C.

As you study ancient myths and legends about creation, you come to understand that they all are based on the same patterns of good and evil, etc.

The same soul who was Enoch the Prophet was also Thoth, Hermes, Metatron, among others who allegedly wrote 'Books about the Sacred Knowledge of Creation'. These creational stories are based on patterns of geometry that repeat in cycles through the concept of TIME.

In the Qur'an, Enoch is called Idris. In the bible he is sometimes called Akhnookh. He was a man of truth and a prophet. We raised him to a high station. Surah 19: 56-57

According to the biblical narrative (Genesis 5:21-24), Enoch lived 365 years, far less than the other patriarchs in the period before the Flood. Enoch allegedly walked with God who turned him into the archangel Metatron.

He called the people back to his forefathers' religion, but only a few listened to him, while the majority turned away. According to the Talmud Selections (pp. 18-21) when the people went astray, Enoch who lived a pious life in seclusion was given prophethood. He came among the people and by his sermons and speeches made the people give up the idolatory and obey the Command of God. Enoch ruled them and during his reign there was peace and justice.

Prophet Enoch and his followers left Babylon for Egypt. There he carried on his mission, calling people to what is just and fair, teaching them certain prayers and instructing them to fast on certain days and to give a portion of their wealth to the poor.

Enoch was the first to invent books and writing, much like Thoth the scribe.

The ancient Greeks declare that Enoch is the same as Mercury / Hermes Trismegistus writing the Emerald Tablets of Thoth.

Enoch taught the sons of men the art of building cities, and enacted some admirable laws. He discovered the knowledge of the Zodiac, and the course of the Planets; and he pointed out to the sons of men, that they should worship God, that they should fast, that they should pray, that they should give alms, votive offerings, and tenths. He reprobated abominable foods and drunkenness, and appointed festivals for sacrifices to the Sun, at each of the Zodiacal Signs.

Enoch's name signified in the Hebrew, Initiate or Initiator. The legend of the columns, of granite and brass or bronze, erected by him, is probably symbolical. That of bronze, which survived the flood, is supposed to symbolize the mysteries, of which Masonry is the legitimate successor from the earliest times the custodian and depository of the great philosophical and religious truths, unknown to the world at large, and handed down from age to age by an unbroken current of tradition, embodied in symbols, emblems, and allegories.

There was a substantial Zoroastrian Influence on Judaism when Jewish exiles were exposed to the Persian religion during the Babylonian captivity. Some Jews adopted Enochian tradition in Babylon during the Exile and brought it back to Canaan when Cyrus gave them leave to Return. The Enochian Jews were detested by the priesthood in Jerusalem, and they were forced to flee into the desert before 300 BCE. Naturally, they supported the Maccabees during the uprising of 165 BCE. The Enochians at Qumran 'updated' the text to include Judah the Hammer in the big story.

The last of the Essene stragglers buried the secret book in Cave IV at Qumran c.70 CE. The urban Christians and Jews of the Near East rejected it. The authors of the Apocalypse rewrote and retitled it, but they didn't understand the heptadic structure of the original lines, the arrangement of sevens. Only the students of the Merkabah in Babylonia possessed the key to the Enochian mystery.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

THE BOOK OF ENOCH

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The Book of Enoch is a pseudo-epigraphal work that claims to be written by a biblical character. It was not included in either the Hebrew or most Christian biblical canons, but could have been considered a sacred text by the sectarians. The original Aramaic version was lost until several Dead Sea Scroll fragments were discovered in Qumran Cave 4 - providing parts of the Aramaic original.

This fragment reads;

Humankind is called on to observe how

unchanging nature follows God's will.

The Book of Enoch was first discovered in Abyssinia in the year 1773 by a Scottish explorer named James Bruce. In 1821 The Book of Enoch was translated by Richard Laurence and published in a number of successive editions, culminating in the 1883 edition.

Enoch acts as a scribe, writing up a petition on behalf of the fallen angels, or fallen ones, to be given to a higher power for ultimate judgment.

Christianity adopted some ideas from Enoch, including the Final Judgment, the concept of demons, the origins of evil and the fallen angels, and the coming of a Messiah and ultimately, a Messianic kingdom.

The Book of Enoch was removed from the Bible and banned by the early church. Copies of it were found to have survived in Ethiopia, and fragments in Greece and Italy.